Complications of anesthesia (sedation during surgery) occur in all patient populations, including those with Down syndrome. It just so happens that some anesthesia complications are more likely to occur in individuals with Down syndrome than their peers without Down syndrome. An awareness of these more common complications can help anesthesia providers plan safer experiences for people with Down syndrome. Planning for a safe anesthesia or sedation scenario requires evaluation of the patient and review of relevant history by trained anesthesia personnel. Direct consultation with an anesthesiologist well before a planned procedure may be necessary if medical or behavioral histories are complicated.

Why Would an Individual With Down Syndrome Need Anesthesia?

40-60% of infants born with Down syndrome have significant cardiac anomalies, most of which require early surgical intervention. In fact, one of the primary contributing factors in survival statistics since the 1960s has been more aggressive early cardiac intervention. Other congenital (present at birth) issues requiring early surgical intervention in Down syndrome populations include esophageal, gastrointestinal, and urinary tract problems. Correction of these problems and early, aggressive developmental therapy contribute to remarkably longer, more community-involved, and more productive lives for people with Down syndrome. Overcoming these major health conditions also means a higher probability of living long enough to develop other chronic health problems that can potentially require surgical intervention, such as illnesses or conditions of the eyes, ears, and joints – just like peers without Down syndrome.

What About Down Syndrome Is Most Likely to Affect Anesthesia Safety?

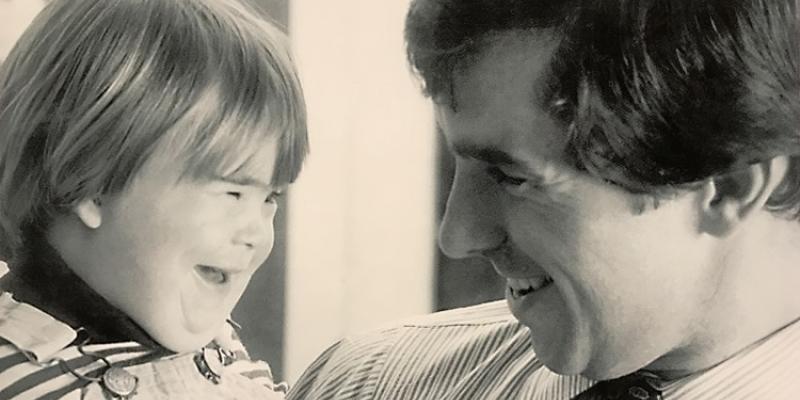

The better we are at communicating our needs, the more comfortable we are transitioning into unfamiliar environments or scenarios. The more difficulty we have communicating with people, the less likely we are to voluntarily go into unfamiliar places or voluntarily interact with strangers. Similarly, those people with Down syndrome who exhibit more expressive language difficulties may also exhibit more anxiety or agitation when placed in unfamiliar or uncomfortable environments – like a doctor’s office or surgery suite. Severe anxiety or agitation sometimes leads to behavior that is unsafe for the person or others nearby, even for loved ones. Anxiety and agitation also produce sympathetic nervous system excitation (“fight or flight”) responses in the body that can contribute to anesthetic complications. For health care professionals, talking to patients and patient caregivers and establishing rapport with them may be enough to lessen patient anxiety or agitation. Preoperative sedatives may also be warranted.

It is important for family and caregivers of patients with Down syndrome to exhibit calm and encouraging emotional behavior during pre-anesthetic periods of evaluation and preparation. Receptive communication skills of people with Down syndrome are often more developed than expressive capabilities; people with Down syndrome are able to detect anxiety and agitation in their caregivers, and will react to what they detect. If family members are able to remain calm, then the patient is more likely to remain calm. If caregivers are anxious or agitated, then the patient will be anxious or agitated. It is always appropriate to feel and express concern for loved ones, but family members need to remember that their loved ones tend to echo the family’s own anxieties – and, rarely, those echoes can cause behavioral avalanches.

Lastly, communication difficulties can make it harder for patients with Down syndrome to describe when they are in pain or feel nauseated, and they often have difficulty giving specifics about their pain (e.g. duration, location, radiation, sensation, and intensity). A patient’s ability to answer, in detail, about their pain greatly aids correct diagnosing of problems and appropriate treatment – especially when it comes to problems related to surgical complications or issues. Inability to communicate in detail increases the risk of misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment.

How Does Sleep Apnea or Airway Obstruction Affect Anesthesia?

People who exhibit obstructive airway problems when sleeping will be especially prone to airway obstruction under sedation and anesthesia. Patients under sedation and anesthesia lose protective airway reflexes (like the cough reflex and gag reflex) and muscle tone, thereby causing airway tissues to come together and briefly close. For people with airway tissues already prone to collapsing during natural sleep states, the loss of airway reflexes under anesthesia is a guarantee of obstruction. Obstructed airways are dangerous because they do not allow delivery of oxygen to the lungs, and airways that remain obstructed can be deadly. Anesthesiologists are, therefore, trained to alleviate airway obstruction by many methods, including intubation (the placement of a breathing tube into the trachea, or windpipe). In rare circumstances, an incision into the neck and trachea (e.g. tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy) may be necessary to establish an open airway.

Some studies suggest that more than 75% of people with Down syndrome will develop obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Causes of OSA in Down syndrome are multiple and additive, including: central apnea, low muscle tone in the mouth and upper airway, poor coordination of airway movements, narrowed air passages in the midface and throat, relative enlargement of the tongue, and hypertrophy (enlargement) of adenoid and tonsillar tissues. Down syndrome-associated OSA occurs regardless of body habitus (fat or thin) and recurs to some degree in over 50% of those who have undergone surgical intervention. OSA places people with Down syndrome at much higher risk for airway obstruction during anesthesia and sedation, including life-threatening obstructive scenarios. It is not routinely necessary to obtain sleep studies prior to sedation or anesthesia, but complicated surgical procedures involving airway structures or previous history of obstructive difficulties during anesthesia may warrant a polysomnography evaluation (sleep study) prior to anesthesia or sedation. Providing the anesthesia practitioner with a relevant history of diagnosis, severity, and treatment of OSA is always valuable in planning safe anesthesia scenarios.

How Is Heart Rhythm Affected by Anesthesia?

Sedation and anesthesia can suppress the sympathetic nervous system (“fight or flight”) responses. This depression of sympathetic responses is desirable and protective in many ways. For example, it decreases the physiologic stress of surgical procedures. Another protective benefit it often offers is a slightly lower heart rate and a lessened likelihood of dangerously fast heart rhythms.

Up to 50% of people with Down syndrome, however, may exhibit bradycardia (slow heart rate) during induction of anesthesia or sedation – even slowing to the point of asystole (stopped heart). Very slow heart rates contribute to low blood pressure, which affects oxygen delivery to vital organs. Slow heart rates can usually be prevented or alleviated with certain medications, but occasionally can be difficult to treat and dangerous to the patient. Children with Down syndrome are probably more prone to exhibit bradycardia with anesthesia than adults, but the risk is significant across age ranges. Most anesthesiologists are trained to consider this risk and prepare for possible treatment, but it’s worth discussing whenever a patient with Down syndrome is considering procedures that require sedation or anesthesia.

Additionally, abnormalities of the valves in the heart, especially mitral valve prolapse (MVP), occur in about 50% of adolescents and adults with Down syndrome. In fact, most adults with Down syndrome who have valve problems do not have histories of congenital heart disease, and half of those adults living with valvular disease may be undiagnosed. Cardiac valve problems can affect hemodynamic stability during anesthesia, including heart rate, heart rhythm, blood pressure, and pulmonary blood pressure. Physical exams, electrocardiograms (EKG), and echocardiograms are some of the tests used to verify the existence and severity of valvular heart disease. Unfortunately, not all adults with Down syndrome will voluntarily participate in such exams without sedation or anesthesia. The suspected existence of valvular heart disease must be communicated to the anesthesiologist prior to sedation or anesthesia.

How Does Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Affect Anesthesia?

Gastroesophageal reflux is an important consideration in anesthesia, as it increases the risk for aspiration (inhalation of foreign material, including stomach contents). As noted earlier, sedation and anesthesia depress the natural protective reflexes that help keep our airways open, allow us to sense aspiration, and help us coordinate cough and swallow actions. Depression of these reflexes means we cannot protect our airway from stomach acid and contents that may reflux into the esophagus when we undergo anesthesia. Those contents can then get into our lungs (aspiration) where irritation, inflammation, and even infection can result. Aspiration during anesthesia induction or emergence periods (going to sleep and waking) also contributes to airway obstruction, including life-threatening airway spasms. Prevention of aspiration is the singular goal of fasting prior to anesthesia and sedation. Required fasting times vary according to the age of the patient and the types of food or liquids ingested.

People with Down syndrome are more prone to experience acid reflux than people without Down syndrome. They also exhibit weaker cough reflexes as compared to their peers without Down syndrome, exhibit higher rates of obesity, and are known to develop much higher rates of pneumonia. This combination of traits places patients with Down syndrome at higher risk for aspiration during sedation and anesthesia and significantly higher risk of complications during the procedures.

How Does Atlantoaxial/Atlantooccipital Instability (AAI/AOI) Affect Anesthesia?

People with Down syndrome are more prone to develop AAI or AOI (instability of upper neck and head-neck joints), which places them at higher risk for catastrophic spinal cord injury. Maneuvering the head and neck to open obstructive airways and to place airway devices, including endotracheal tubes, is an expected part of nearly every sedation and anesthetic. As mentioned earlier, one of the complicating realities of anesthesia is the loss of protective reflexes, sensation, and the ability to feel or express pain. If someone has AAI/AOI, routine manipulation of the neck – as occurs during sedation and anesthesia – can be very dangerous. Maintaining a neutral head and neck position during airway instrumentation or intubation is usually sufficient to prevent spinal cord injury, but such positioning can interfere with the anesthesiologist’s ability to successfully intubate or otherwise keep a patient with Down syndrome’s airway open.

Preoperative neck films, computed tomography (CT), or medical clearance from a neurologist or neurosurgeon may be necessary prior to anesthesia.

What Does Airway Size Have to Do With Anesthesia?

People with Down syndrome typically have smaller glottic and tracheal diameters (voicebox and windpipe sizes) than their peers without Down syndrome, and they also exhibit higher incidences of subglottic stenosis and tracheomalacia (abnormally narrowed or soft windpipe). When undergoing endotracheal intubation for anesthesia, patients with Down syndrome require smaller endotracheal tubes (breathing tubes) than their peers who do not have Down syndrome. It is important for the intubating practitioner to remember this principle in order to avoid unnecessary tracheal, vocal cord, or voice box injury.

What Other Issues in Down Syndrome Affect Anesthesia?

Difficult intravenous (IV) access related to obesity and xerodermia (dry, thickened skin) can complicate delivery of anesthesia and pain medicines. Other conditions that must be considered when planning anesthesia and sedation include: autoimmune disorders (such as celiac disease and hypothyroidism), diabetes, dementia, depression, epilepsy, hypotonia, obesity, and osteoporosis. Some of these conditions occur at higher frequencies in people with Down syndrome, but most occur at similar rates compared to other populations. Some conditions people with Down syndrome are less likely to exhibit than people without Down syndrome include asthma, hypertension, coronary or peripheral vascular disease, and solid organ tumors.

Conditions affecting vision or hearing will further complicate communication problems that may already be present in people with Down syndrome. As noted earlier, such communication problems can contribute to anxiety, agitation, and behavioral issues in the surgical setting.

Anesthesia personnel will ask a lot of questions about the patient’s medical and surgical histories, some of which may be historically remote in occurrence. The key to understanding why anesthesia providers want so much information is knowing that many remote conditions (e.g. AAI/AOI, congenital heart disease, difficult intubation, rheumatic fever, or malignant hyperthermia) can lead to sequelae (consequences of injury or disease) – even apparently unsymptomatic sequelae – that directly affect anesthetic safety.

***

NDSS thanks special guest author James E. Hunt, M.D of Arkansas Children’s Hospital for this article. Special thanks also to Drs. Timothy Martin (MD, MBA, Professor, Chief of Pediatric Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and Vice-Chair of UAMS Department of Anesthesiology) and Michael Schmitz (MD, Director of Pediatric CV Anesthesia for Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Professor in UAMS Departments of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics).

Additional Resources

External Resources

- James E. Hunt, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology

Department of Anesthesiology

UAMS College of Medicine

Division of Pediatric Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

Co-Director of Burn Anesthesia

Coordinator of Anesthesia Services for UAMS Genetics Clinic

Arkansas Children’s Hospital

1 Children’s Way, Slot 203

Little Rock, AR 72202

huntjamese@uams.edu

- University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Adult Genetics Clinic/Down syndrome Clinic

Freeway Medical Tower (5800 W. 10th), 6th floor, Suite 605

Little Rock, AR 72201

501-526-4020